Everyone’s talking about this book, and it has to be said that I’m not the sort of person who reads the books that everyone is talking about (case in point, ’50 Shades of Nonsense’). However, I saw the author in person a few months ago and, you know, he was kinda hot, so I gave in to the hype and decided to see what all the fuss was about. I was not disappointed.

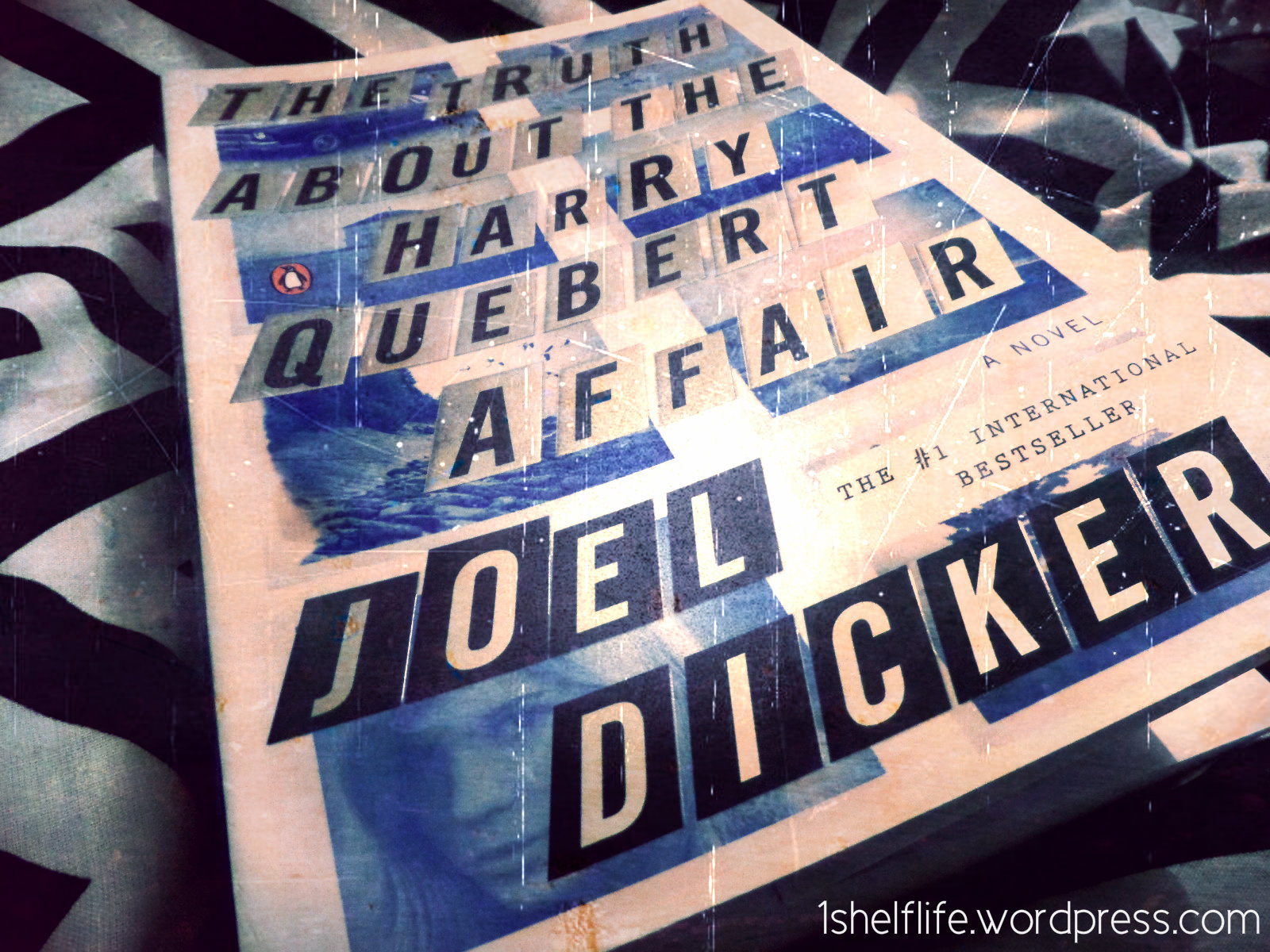

This is the US edition that I picked up on holiday.

I cannot remember the last time that I was so absorbed in a book that I actually switched off my Netflix. I was so desperate to see how the book ended that I stayed up until 3:30 a.m. on a Sunday night/Monday morning (knowing full well I would suffer at work the next day) just inhaling the book. That I am a slow reader is a fact. That I finished this 640 page novel in one busy weekend is another fact. This is such an effortless read, the pages simply turn themselves.

If you’re not one of those people talking about this book, then let me give you a bit of background information. The book was first published in France in 2012 and has since sold over 2 million copies, been translated into over 30 languages and has also won some literary prizes in France. Plus, the writer is only now 28 years old and looks like this:

I have come across uglier writers. (c) Jeremy Spierer

Anyhow, back to the book. Marcus Goldman is our lazy but likeable protagonist who has achieved continuous success throughout his life, due to the very simple fact that he only competes in situations where he’s guaranteed to win, against people who he knows to be weaker than he is (and the one time he saw that he was not going to win a race, he chose to deliberately break his leg rather than allow the illusion of “Marcus the Magnificent” to be tarnished):

‘In order to be magnificent, all that was needed was to distort the way others perceived me; in the end, everything was a question of appearances.’

The book opens in New York in the spring of 2008 where Marcus is experiencing severe writer’s block. His publishers are on his case and are threatening to sue if he doesn’t deliver the follow up to his wildly successful debut. In search of inspiration, Marcus goes to New Hampshire to visit his old college professor and mentor, Harry Quebert, a novelist still famous for a single book he wrote in the 70s. This trip doesn’t work for Marcus’s creativity so he goes back to New York, resigned to the fact that his career is now over.

Except, a few weeks later, he receives an urgent call from his agent urging him to switch on the TV. Harry’s in trouble and is all over the news: The body of a 15 year old girl who went missing 33 years ago has been found buried in his back yard. Buried with her is the original manuscript of Harry’s famous novel, The Origin of Evil. Maybe, now, Marcus has something to write about. Harry is quickly arrested and admits to having had an affair with the young girl. The national media hang him out to dry – not only is he a murderer, but a paedophile to boot. There is one thing though: Harry swears to Marcus that he did not kill Nola Kellergan, in fact, she was the love of his life. Marcus, eager to clear his friend’s name, heads back to New Hampshire to start his own investigation into what really happened on August 30, 1975, the day Nola went missing, the day the little town of Somerset, New Hampshire lost its innocence.

On the surface, Somerset is a quaint little New England town, but as the investigation progresses, one has to wonder if, perhaps, Somerset hadn’t lost its innocence long before Nola went missing. Marcus stays in Harry’s house receiving threatening mail as he continues to uncover the truth about the affair, writing his surefire bestseller as he goes along. This novel is as much about publishing and the writing process as it is about the Kellergan murder (very self-reflexive, metafictional stuff). There’s an interesting cast of characters here, a couple of which were slightly exaggerated and caricaturish, but that didn’t stop me laughing out loud at the (often dark) humour exhibited in their conversations. There’s the chauffeur with a distorted face, the pastor with the Harley motorbike and, of course, the seemingly unknowable Nola Kellergen herself, the object of Harry’s obsession. I was often struck by how young Nola came across. She would accuse Harry of being ‘mean’ to her and once said of God, “If you believe in Him, I will too.” On these occasions I found it difficult to understand why Harry was so consumed by her, why ‘once she had entered [his] life, the world could no longer turn properly without her.’ How could an academic have a relationship with someone so naive and childlike? But then we are told by a Somerset local:

On the surface, Somerset is a quaint little New England town, but as the investigation progresses, one has to wonder if, perhaps, Somerset hadn’t lost its innocence long before Nola went missing. Marcus stays in Harry’s house receiving threatening mail as he continues to uncover the truth about the affair, writing his surefire bestseller as he goes along. This novel is as much about publishing and the writing process as it is about the Kellergan murder (very self-reflexive, metafictional stuff). There’s an interesting cast of characters here, a couple of which were slightly exaggerated and caricaturish, but that didn’t stop me laughing out loud at the (often dark) humour exhibited in their conversations. There’s the chauffeur with a distorted face, the pastor with the Harley motorbike and, of course, the seemingly unknowable Nola Kellergen herself, the object of Harry’s obsession. I was often struck by how young Nola came across. She would accuse Harry of being ‘mean’ to her and once said of God, “If you believe in Him, I will too.” On these occasions I found it difficult to understand why Harry was so consumed by her, why ‘once she had entered [his] life, the world could no longer turn properly without her.’ How could an academic have a relationship with someone so naive and childlike? But then we are told by a Somerset local:

‘That girl was madly in love with Harry. What she felt for him was something I had never felt myself, or I couldn’t remember ever having felt, for my own wife. And it was at that moment that I realised, thanks to a fifteen-year-old girl, that I had probably never been in love. That lots of people have never been in love. That they make do with good intentions; that they hide away in the comfort of a crummy existence and shy away from that amazing feeling that is probably the only thing that justifies being alive.’

The narrative flicks back and forth between 1975 and 2008, slowly piecing the facts together. Or at least what we believe to be facts. There are so many twists and turns in this novel so be warned that as soon as you’re convinced of one thing, several chapters later you will learn something new that weakens your conviction. This is your classic whodunnit at its best. There are 31 chapters in this book, and Dicker has very cleverly started off with chapter 31, making the reader work their way down to chapter 1 where we finally find out:

The million dollar question

The last chapter is filled with pleasing revelations that allow everything to finally lock into place. It is only then that you’re able to let out the breath that you didn’t even realise you were holding.

I, personally, didn’t understand why everyone made such a big deal about ‘The Girl with the Dragon Tattoo‘. I’ll admit that I haven’t read it, but I did recently watch the film on a rainy Netflix weekend and was left perplexed as the end credits rolled: the big twist in this blockbuster thriller is that the girl who everyone thought was dead had actually escaped in the boot of a car? Really?! That was Larsson’s great achievement? If critics have time to commend Larsson, then the same (actually, more) credit is due to Dicker. His story is much more layered, more intriguing and a hell of a lot more clever. Fact.

The British critics haven’t been very nice about this book (pretty brutal, actually), and I don’t think they’re being fair to Dicker. I do imagine that some of the elegance of the prose was lost in translation so, yes, there were one or two occasions when I felt the writing felt a bit basic (descriptive passages in particular), where the dialogue didn’t ring quite true, but did this detract from my overall enjoyment of the book? Not at all. I was, honestly, gripped. I sighed through my weekend engagements, my eyes lingering longingly on the book nestled in my bag, made my excuses to leave early and kept reading as I changed lines on the tube, unapologetically bumping into people as I walked. I just HAD to to know what would happen next, I had to finish it. And was then sad when I did. In the words of Harry Quebert:

The ending of a good book

The bottom line is that this is a brilliantly plotted murder mystery, cleverly constructed. Though it might not be as literary as the French claimed it was, it ultimately does not matter because it’s a bloody good read.